Pornography Use Effects

A synthesis of quantitative and neuroscience studies (2015-2020) by GuardYourEyes

| Population | Diagnostics | Study Type | Effects |

| Teenagers

Adults Treatment-seeking Couples |

Exposure to pornography / sexually explicit media

Problematic pornography use (PPU) Masturbation (solo or excessive) Compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) |

Survey

Clinical (treatment) Longitudinal Dyadic (couples), daily diary fMRI / neuroscience Meta-analytic |

Personal

addiction psychological distress cognitive performance Relational satisfaction Public health risky sexual behaviors sexually transmitted infections (STIs) teen or unplanned pregnancy |

Summary

Background

Pornography use has been recently defined as “a common but stigmatized behavior, in which one or more people intentionally expose themselves to representations of nudity which may or may not include depictions of sexual behavior, or who seek out, create, modify, exchange, or store such materials” (Kohut et al., 2020, p. 733).

In recent nationally representative studies of Australian, US, and Polish participants, 70% to 85% of participants have ever used pornography in their lifetime with 85% of males reporting lifetime pornography use (cf. Bőthe et al, 2020b).

10.3% of men and 7.0% of women endorsed clinically relevant levels of distress and/or impairment associated with difficulty controlling sexual feelings, urges, and behaviors in a recent US nationally representative sample (Dickenson, 2018).

Objective

To determine the effects of pornography use at the personal, relational and public health/societal level.

Search methods

Google Scholar, PubMed, and ScienceDirect were used to identify studies. The reference lists of relevant articles was also consulted.

Inclusion criteria

Criteria for selecting studies included:

- Recency: published between 2015 to date (Aug 2020, including in press articles)

- Quantitative design: reported data on quantitative assessments of 1) pornography use or exposure and 2) effects of pornography use or exposure.

- High quality methodology: robust sampling and data analysis methods.

Data collection and analysis

Steps:

- 20 studies that have matched the inclusion criteria have been analysed in-depth and summarised

- 7 studies deemed highly relevant for the GYE community (e.g. population similarity) were included in the present synthesis.

Studies have been assessed for methodological quality according to criteria specified by Fisher and Kohut (2020), namely:

AA - meta-analytic or systematic review studies

A - longitudinal, experimental or neuroscience studies

B - correlational studies

C - descriptive studies

A “+/-” indicator was also used to denote a large or small number of study participants. Key findings are presented below.

Key findings

| Crt. | Study | Population | Study design + sample size | Predictor | Effects | Effect size | Strengths & limitations | Study

quality (A-C) |

| 1 | Lin et al., 2020 | Teenagers / young adults, Taiwan | Longitudinal ( Taiwan Youth Project) with 10-wave measurements, first wave in 7th grade (mean age = 13.3) and the tenth wave in emerging adulthood (mean age = 24.3) | Exposure to sexually explicit media | - earlier onset of first sexual intercourse (first sexual act before age 17)

- unsafe sex (e.g., inconsistent condom use) - more sexual partners (i.e., high partner change rate) - sexually transmitted infections (STIs; e.g., gonorrhea) by association with risky sexual behavior - unplanned or teen pregnancy (by association with risky sexual behavior) |

Large | No serious limitations | A+ |

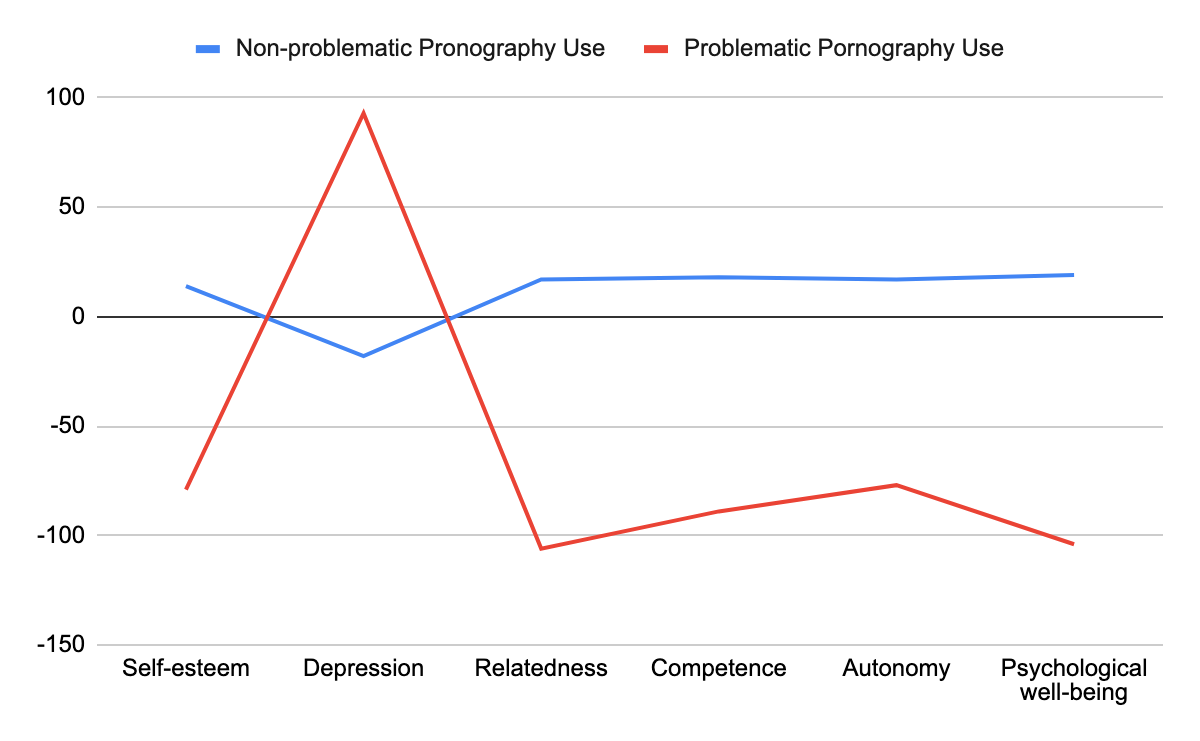

| 2 | Bőthe et al., 2020a | General population, large sample (online) | Correlational, 3 nonclinical samples recruited from general websites and a pornography site (study 1: N = 14,006; study 2: N = 483; study 3: N = 672) | Problematic, high frequency use of pornography | - depressive symptoms

- lower self-esteem - relatedness frustration (e.g. feelings of exclusion from the group one wants to belong to) - lower relatedness satisfaction (e.g. feeling that the people one cares about also care about him/her) - competence frustration (e.g. serious doubts about whether one can do things well) - affected well-being (overall frustration in the basic psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness and competence) |

Large | High generalizability (large, non clinical sample)

Correlational (no causality can be inferred) |

B+ |

| 3 | Gola et al., 2017 | Treatment seeking heterosexual males | Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study among 28 heterosexual males seeking treatment for problematic pornography use and a control-group with 24 heterosexual males without problematic pornography use | Problematic pornography use | - addiction-like effects

- extended time spent watching pornography - more frequent masturbation |

Large | Small sample size | A- |

| 4 | Perry, 2020 | U.S. nationally representative sample(s) | Correlational, two US national surveys: the 2012 New Family Structures Study (NFSS; N = 1,977) and the 2014 Relationships in America survey (RIA; N = 10,106) | Pornography use

Solo masturbation (with or without pornography use) |

Slight positive association between relational happiness and pornography use (once masturbation and gender differences are accounted for)

Negative association between solo masturbation and relational happiness (for both men and women) |

Small for pornography-relational happiness association (positive)

Large for masturbation-relational happiness (negative) |

The surveys did not measure if pornography was watched with the partner or solo | B+ |

| 5 | Dickenson et al., 2018 | U.S. nationally representative sample(s) | 2325 adults (1174, 50.5% female; mean age = 34 years) | Compulsive sexual behaviour (difficulty controlling one’s sexual feelings, urges, and behavior) | Distress: feeling ashamed because of the sexual behavior, engaging in sexual behavior as a means of emotion regulation

Psychosocial impairment: social, interpersonal, and occupational consequences. |

Large | Correlational study, causality cannot be inferred. | B+ |

| 6 | Castro-Calvo et al., 2020 | General population, large sample (Spain) | Two independent community samples: sample 1 included 1,581 university students (females = 56.9%; mean age = 20.58) whereas sample 2 comprised 1,318 community members (females = 43.6%; mean age = 32.37) | Compulsive sexual behavior | More depressive and anxious symptoms

Poorer self-esteem |

Large for depressive symptoms

Small to moderate for anxiety symptoms Small to moderate for self-esteem |

Correlational study, causality cannot be inferred. | B+ |

| 7 | Sinke et al., 2020 | Treatment seeking heterosexual males | Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study with a working memory performance task with neutral or pornographic pictures in the background was employed in 38 patients and 31 healthy controls | Hypersexual behavior | Poorer mental performance (working memory) in terms of slower reaction times (decrease of performance was related to pornography consumption in the last week) | Large | participant inclusion criteria were defined according to Kafka’s criteria for hypersexual behavior which do not directly translate to ICD-11 criteria | A- |

Conclusions and discussion

At the personal level, common effects of pornography use include deprecated mental health and well being (i.e. poorer self-esteem, depression and frustration in psychological needs), although the relationship is not yet clear (e.g. are people more depressed because of using pornography or depression makes people more prone to use pornography?).

At the relational level, pornography use can affect relationship satisfaction, especially if masturbation is involved, although studies with couples (not just one partner) have reported different results.

At public health/societal level, common effects of pornography use include more risky sexual behaviors (e.g. unsafe sex), having sex at a younger age and STIs, with relatively conclusive results.

An increasing number of studies from neuroscience show that pornography can result in a serious addiction similar to gambling or substance use addictions. Moreover, a recent fMRI study suggests that pornography effects extend beyond addiction to affect cognitive performance, such as working memory.

A large number of studies on pornography effects have limitations such as using a correlational design. A correlational design can only reveal associations between variables or presumed effects, not causal effects. Another important limitation in the literature is the lack of multiple validated measures of pornography use and effects, aligned with the ICD-11 criteria for compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) (Kohut et al., 2020).

Overall, the studies reviewed in this sythesis show that pornography use may contribute to lasting cognitive, affective, and behavioral changes with implications at personal, relational and societal levels.

References

Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Potenza, M.N., Orosz, G. and Demetrovics, Z., 2020a. High-frequency pornography use may not always be problematic. The Journal of Sexual Medicine.

Bőthe, B., Tóth-Király, I., Griffiths, M.D., Potenza, M.N., Orosz, G. and Demetrovics, Z., 2020b. Are sexual functioning problems associated with frequent pornography use and/or problematic pornography use? Results from a large community survey including males and females. Addictive Behaviors, p.106603.

Castro-Calvo, J., Gil-Llario, M.D., Giménez-García, C., Gil-Juliá, B. and Ballester-Arnal, R., 2020. Occurrence and clinical characteristics of Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD): A cluster analysis in two independent community samples. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), pp.446-468.

Dickenson, J.A., Gleason, N., Coleman, E. and Miner, M.H., 2018. Prevalence of distress associated with difficulty controlling sexual urges, feelings, and behaviors in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), pp.e184468-e184468.

Fisher, W.A. and Kohut, T., 2020. Reading pornography: methodological considerations in evaluating pornography research. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(2), pp.195-209.

Gola, M., Wordecha, M., Sescousse, G., Lew-Starowicz, M., Kossowski, B., Wypych, M., Makeig, S., Potenza, M.N. and Marchewka, A., 2017. Can pornography be addictive? An fMRI study of men seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(10), pp.2021-2031.

Lin, W.H., Liu, C.H. and Yi, C.C., 2020. Exposure to sexually explicit media in early adolescence is related to risky sexual behavior in emerging adulthood. PloS one, 15(4), p.e0230242.

Perry, S.L., 2020. Is the link between pornography use and relational happiness really more about masturbation? Results from two national surveys. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(1), pp.64-76.

Sinke, C., Engel, J., Veit, M., Hartmann, U., Hillemacher, T., Kneer, J. and Kruger, T.H.C., 2020. Sexual cues alter working memory performance and brain processing in men with compulsive sexual behavior. NeuroImage: Clinical, p.102308.

Appendix

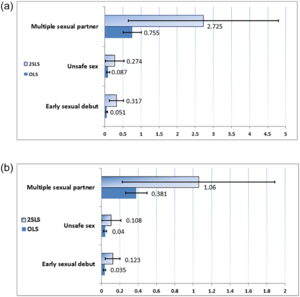

Figure 1. Sexually explicit media exposure and risky sexual behavior (Lin et al., 2020)

| A consistent finding (Fig 1 on the left) was that sexually explicit media exposure in early adolescence was significantly related to risky sexual behaviors in late adolescence.

Specifically, the results revealed that relative to their counterparts, adolescents exposed to sexually explicit media in early adolescence were 31.7% and 27.4% more likely to engage in sexual behavior before age 17 and to engage in unsafe sex, respectively (2SLS estimation). Moreover, these youths had on average three or more sexual partners by age 24.

|

Figure 2. Group differences in pornography use (adapted from Bőthe et al., 2020a)